The changing of protein structures with heat, salt, or acid.

What are the fundamentals of coagulation?

Coagulation is what happens to as become fully cooked. When you expose protein-rich foods to salt, acid, or heat, they drastically change their structure (think of raw vs. cooked chicken).

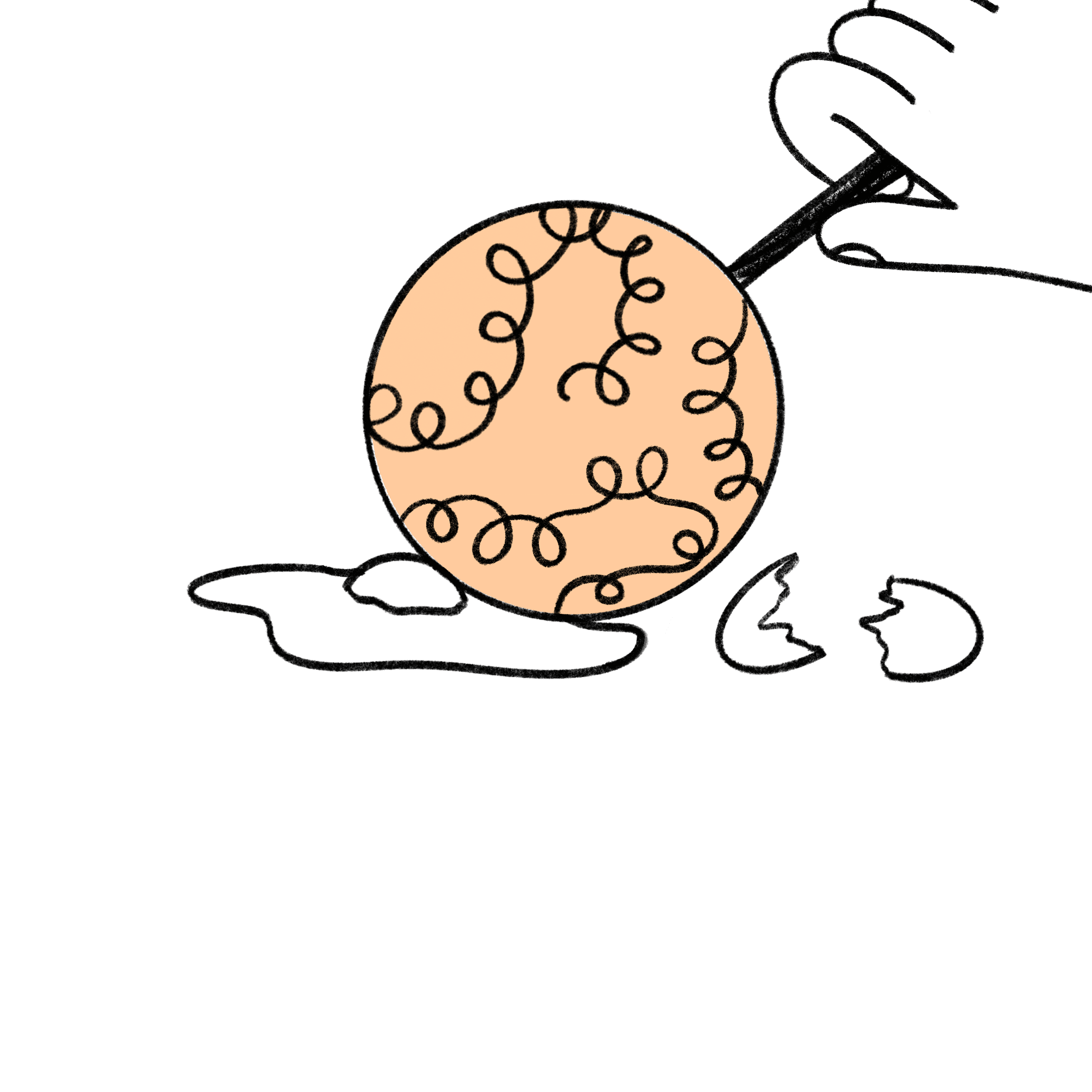

Protein molecules (amino acids) are shaped like coiled or folded strands. These easily unravel, or denature, when exposed to salt, acid, or light heat (starting at around 140-180°F/60-80°C). As cooking processes expose these denatured proteins to higher temperatures, the uncoiled strands begin to link up with one another, resulting in coagulation, or the final cooked protein stage.

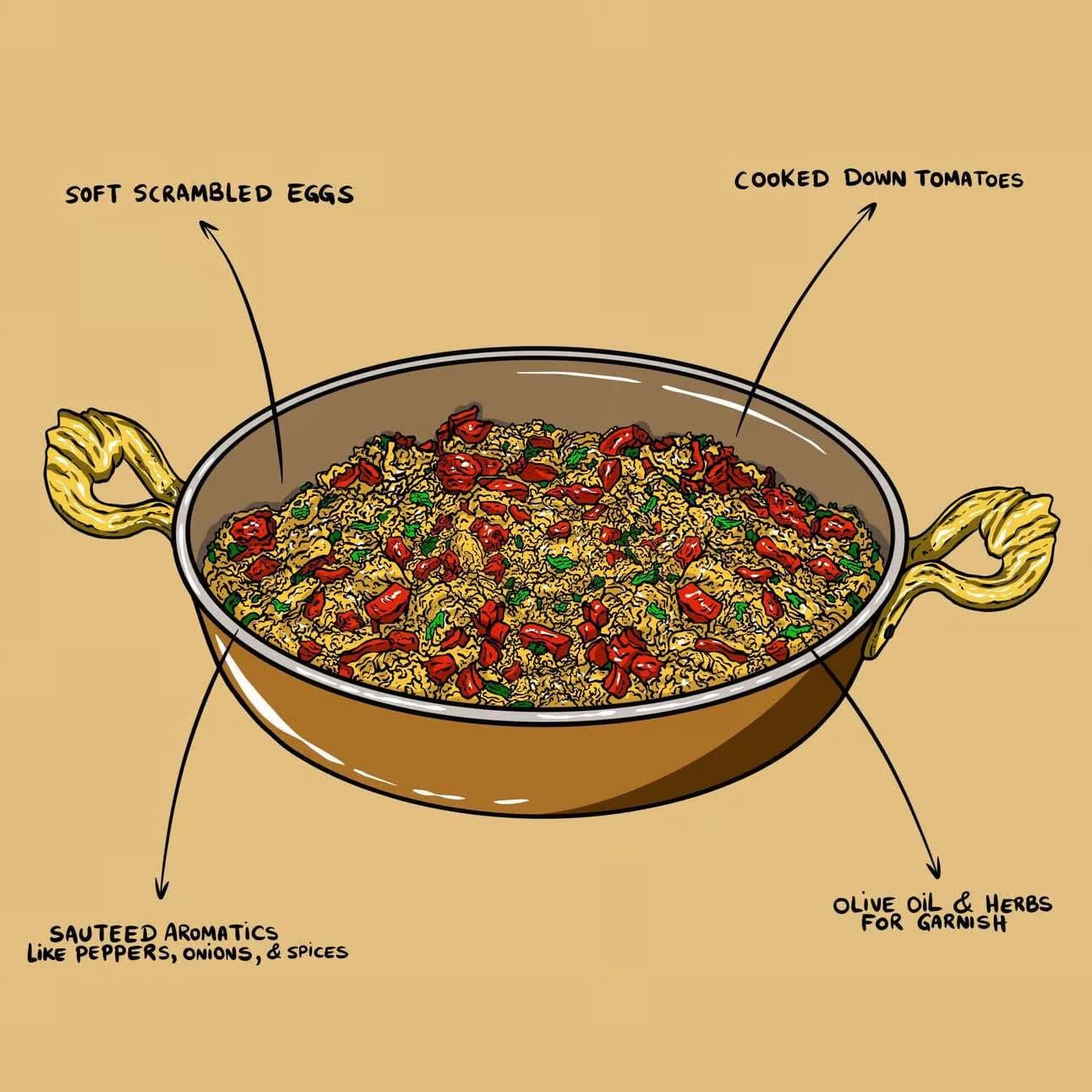

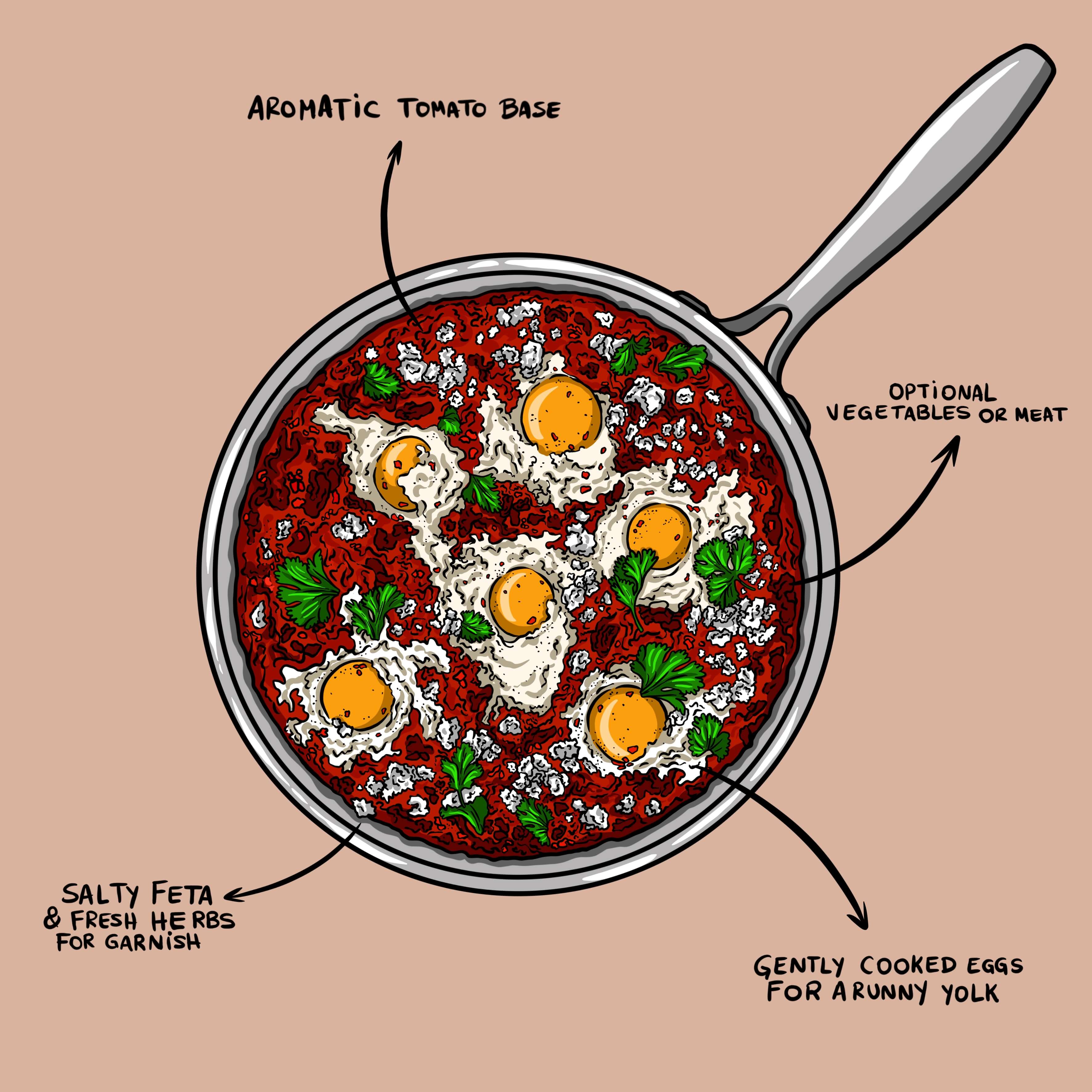

- Think of how scrambled eggs go from being raw and gloopy to thin and watery over low heat, and then solid as they cook and set — that’s their protein strands denaturing but then coagulating together to form curds.

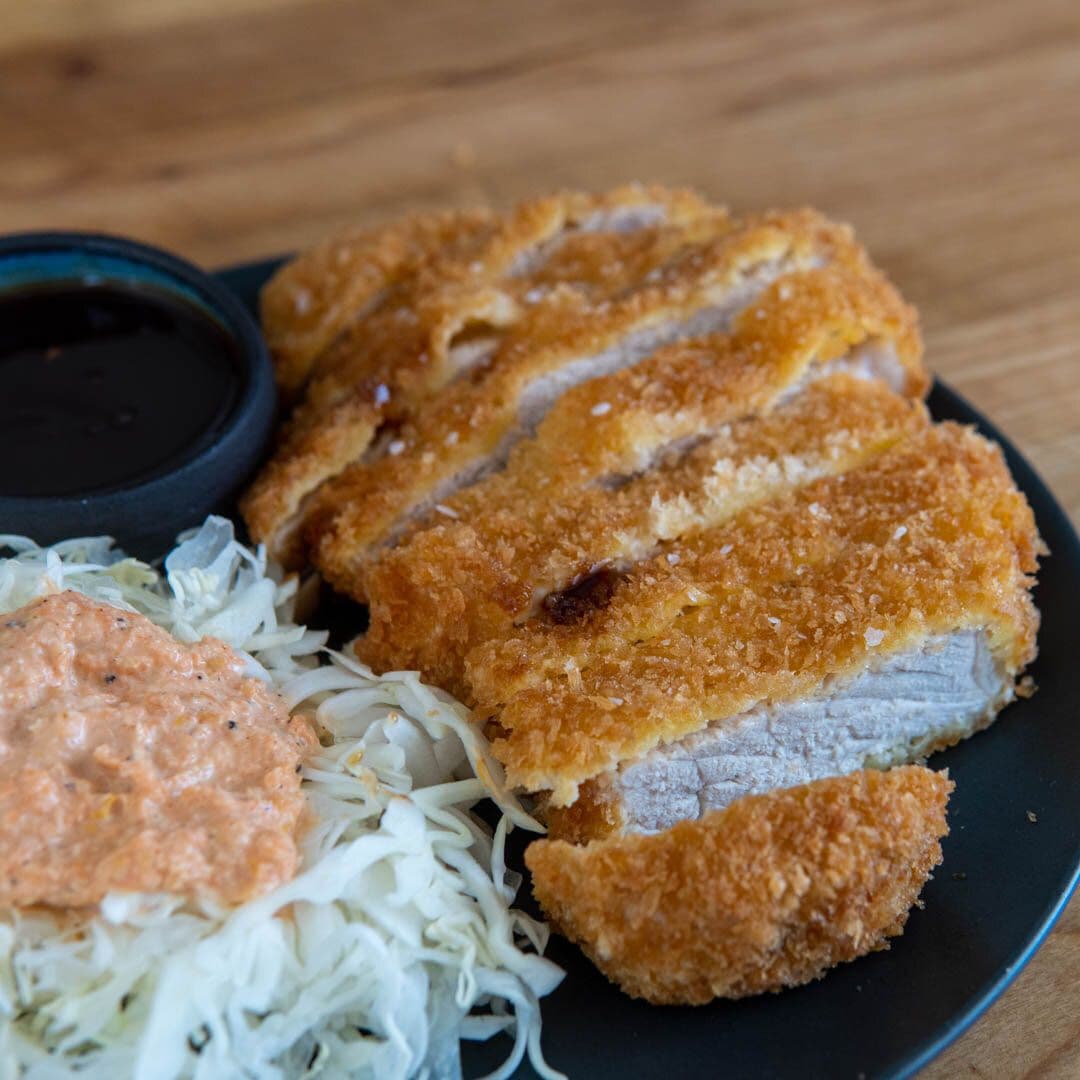

- This process can be taken too far, such as overcooking a steak, where the coagulated proteins become so tightly bound that they push out internal water content, leading to a dry, rubbery, or chewy texture.

Note: Different protein types, like collagen (a connective tissue), break down in slightly different ways. When exposed to heat over a long period, the collagen changes its structure into soft and tender gelatin.

How is coagulation different from ? Don’t confuse any of these processes with gelation: coagulation relies on a cooked protein network to solidify dishes, while gelation uses starch-based thickeners, like pectin.

➡️ Catalysts: Heat, change in PH, or salt

🛠️ Relevant techniques:

🔬 Relevant molecules:

Example foods

- Braised pork shoulder

- Seared chicken thighs

- Scrambled eggs

- Custard

- Ceviche

How does coagulation affect the elements of flavor?

In order of importance:

— While denaturing loosens protein strands, coagulation firms everything back up into a matrix. Gone too far, and the process can squeeze out water content contained by the ingredient: overcooked eggs leak out water, and an overdone steak loses its moisture and becomes dry.

— Denaturing then coagulating proteins with heat, salt, or acid has allowed humans to preserve and digest proteins for thousands of years. From an emotional perspective, we can be appetized or disgusted by the state of a protein. In general, humans prefer firm, cooked foods over raw or mushy proteins.

— We use our eyes to determine how a protein has been prepared, and experience denatured proteins visually before their texture hits our mouth. A perfectly cooked medium-rare steak is first evaluated by color. A flan is checked with a jiggle or a spoon — we can see if the milk and egg proteins have coagulated enough by sight.

— Whether they are cooked with heat or cured with salt or acid, denatured/coagulated proteins can be easier or safer to digest than raw proteins.

— Denaturing/coagulating proteins doesn’t directly affect their taste. In general, proteins are mostly tasteless on their own. However, because denaturing proteins usually happens with heat, other reactions like the Maillard reaction might be happening simultaneously, which affects taste.

— Denaturing/coagulating proteins doesn’t directly affect their aroma. However, because denaturing proteins usually happens with heat, other reactions like the Maillard reaction might be happening simultaneously, which do affect aroma.

Coagulation in Action

The Mouthful

Become a smarter home cook every Sunday

Join 60,000+ home cooks and get our newsletter, where we share:

- Recipe frameworks & cooking protocols

- Food trends explained

- Meal recommendations

- Q&A from expert home cooks

We hate spam too. Unsubscribe anytime.